The English Civil Wars were a tumultuous time in British history, filled with bloodshed and discord. The conflict had been building up for years, with tensions running high between the monarchy and Parliament. A Parliament had operated in England since King John (buried in Worcester Cathedral) put his seal on the Magna Carte in 1215. However, Parliament was unpopular with many of the monarchs that followed King John. While King Charles I’s refusal to allow Parliament to sit for over a decade only fueled the flames of discontent.

The English Civil Wars were fought between 1642 and 1651 over the power of the monarchy and the rights of Parliament. It was a time of bitter struggle for absolute supremacy, as supporters of the monarchy of Charles I (and his son and successor, Charles II) faced off against Parliamentarians in England, Covenanters in Scotland, and Confederates in Ireland. The conflicts began on August 22, 1642, when Charles I hoisted his battle standard at Nottingham Castle, declared war against Parliament, and began to raise a Royalist army.

The Parliamentarians were led by Oliver Cromwell, a staunch Puritan who distrusted the Church of England hierarchy and advocated for the abolishment of the episcopate.

The Parliamentarians became known by the insulting name of ‘Roundheads’ due to their short, cropped hair rather than wearing their hair in the long and flowing style of the Royalists. They were also known as ‘Rebels’ by the Royalists.

The Royalists became known as the ‘Cavaliers’ a Spanish name for a horseman. Numerous wealthy noblemen supported King Charles I and brought many of their employees to the Royalist cause.

In 1645, Parliament made a significant decision to develop a full-time professional army, known as the New Model Army. Comprised of dedicated soldiers, known as the ‘Ironsides’ for the armor they wore, this army marked a turning point in the wars. With a well-trained and disciplined force at their disposal, the Parliamentarians were able to make significant strides in their fight against the Royalists.

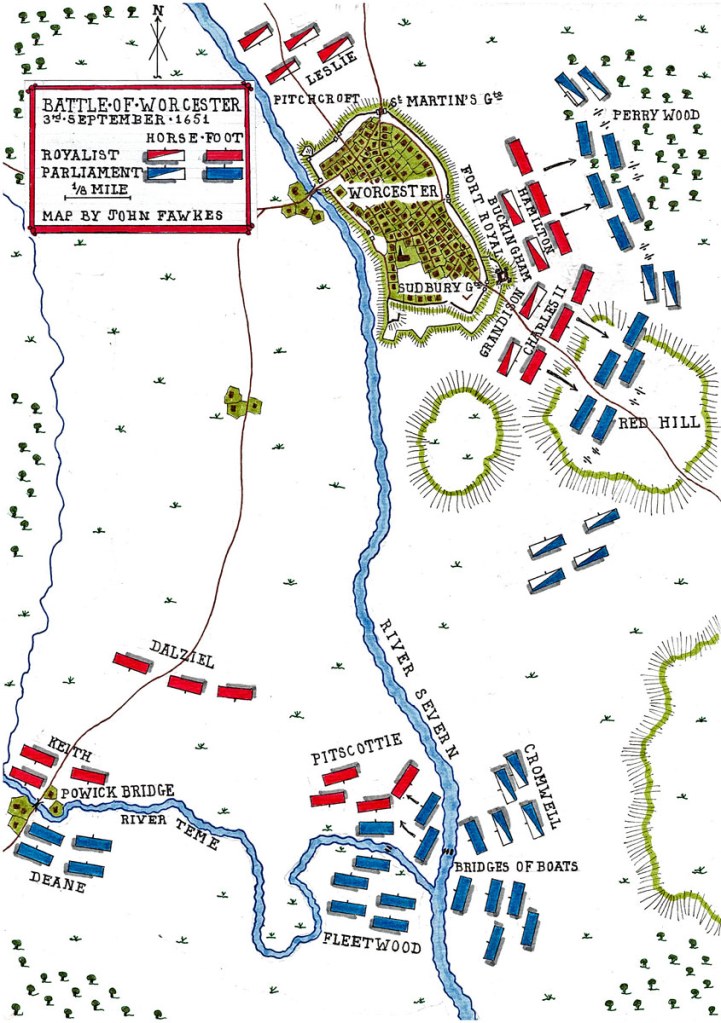

The Battle of Worcester, the last battle of the English Civil Wars, was fought on September 3, 1651; nine years earlier the first substantial action of the wars had taken place barely two miles to the south of the city of Worcester, at Powick Bridge. Whereas that first skirmish had been a dramatic success for Prince Rupert’s Royalist cavalry, by 1651 it was Parliament’s New Model Army that was the dominant military force.

The Royalist forces, predominantly made up of young, unskilled conscripts from villages and clans all over Scotland, found themselves facing a formidable opponent in Cromwell’s well-trained New Model Army.

Following the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Scots recognized his 19-year-old son as King Charles II and agreed to support his claim to the throne in return for political concessions. David Leslie, Lord Newark, an experienced and skillful officer was appointed to raise an army for Charles II. After Charles II was crowned King of the Scots, at Scone, he took command of the army appointing Leslie as his Lieutenant-General. Charles II led an army some 12,000 strong into England in August 1651.

As he advanced through the northern counties Charles II expected his army to be joined by thousands of loyal supporters, eager to join the cause. Not only did the expected recruits not materialize but many of the Scottish stragglers were mopped up by Parliamentarian troops who dogged their steps all the way.

Beleaguered by Cromwell’s forces following behind, after three weeks of rapid marches, on August 22, 1651, Charles II, and his exhausted men, many of them barefoot, limped into Worcester, where the mayor and sheriff proclaimed him King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland. Charles II issued a general pardon for all who had fought against his father during the English Civil Wars, called for his subjects to join him to restore “the quiet, the liberty, and the laws of the English nation,” and rallied his followers in the riverside meadows near Worcester Cathedral.

The brisk marches had taken their toll on the Royalist troops and Charles II decided to rest in the city of Worcester and allow time for other supporters to join him. Perceiving that Charles II’s next move would be against London, Cromwell with some 28,000 troops of the New Model Army, moved to cut off his route to the east at the same time as blocking passage to the west, from where the expected reinforcements were to come.

The tension in the air must have been palpable as the Royalists in Worcester awaited the arrival of the formidable Parliamentary army. Fort Royal was fortified, and bridges over the Severn River were blown up to hinder the enemy’s advance. On August 29, Cromwell’s well-equipped and vastly outnumbering army arrived at Red Hill, just a mile outside the city.

For days, there was a standoff with occasional artillery barrages, but Cromwell held back, biding his time. Charles II began September 3 atop Worcester Cathedral with his generals, watching the approach of Cromwell’s forces and planning their strategy. They knew their situation was desperate, and that for Charles II the outcome of the day would be “a crown or a coffin.”

Charles II liked to gamble. The 21-year-old son of slain English King Charles I was a fixture at the gaming tables and boudoirs of Europe, where he had spent the last half decade in restless exile while his father unsuccessfully sought to hold onto both his crown and his head. Following his father’s execution at Whitehall, London, on January 30, 1649, the young prince had returned to his ancestral home in Scotland, rallying the disaffected Scots to rise against the English Puritans led by Oliver Cromwell, who had decisively defeated them at the Battle of Dunbar on September 3, 1650.

Since being crowned king of England and Scotland on January 1, 1651, Charles II had found little time to pursue his pleasures. With the grudging assistance of Scottish General David Leslie, Cromwell’s bested opponent at Dunbar, the new king had spent the past six months rebuilding his Royalist forces and making plans to recapture the throne and avenge his father. He had cobbled together an army of about 12,000 men, most of them Scots who hoped to forcibly impose their Presbyterian religion on Anglican England. Charles was more or less indifferent to the religious underpinnings of the war — if anything, he tended to favor his Catholic mother’s church — but he had willingly signed a “Solemn League and Covenant” agreeing to promote Presbyterianism as the new state religion once a Stuart sat again on the English throne.

As the sun rose on September 3, marking the anniversary of Cromwell’s victory at the Battle of Dunbar, the Battle of Worcester began. The Parliamentarians, led by Oliver Cromwell, initiated a fierce assault on the city with their battery of fifty-six cannons positioned on Red Hill. In response, the Royalists launched a simultaneous attack on the artillery battery and a fortification near the River Severn. The Parliamentary forces attempted to cross the bridge at Powick, only to be met with fierce resistance from the Scottish troops of Highlanders under the command of Colonel Sir William Keith. The battle on the flat ground around Powick Meadows was brutal, with musketeers and pikemen locked in close combat. Despite their best efforts, the Parliamentary forces were unable to break through the Scottish lines.

The Battle of Worcester thenceforth unfolded on multiple fronts. The Royalists initially had the upper hand, attacking the weakened main Parliamentarian forces to the south and the east. Charles II himself was amid the fighting, leading his troops with courage and determination. However, Cromwell’s men were able to capture Fort Royal, turning its cannons on the King’s army and forcing the Royalists to hastily retreat and scramble to get back within the walls of the city. The Scottish cavalry, under the command of Lieutenant-General Leslie, completely failed to join the battle, a squandered opportunity that could have turned the tide of the battle in favor of the Royalists. With around 28,000 men at his disposal, Cromwell was able to spread his army in a wide arc, trapping the smaller Royalist army within the walls of Worcester. As the city gates were breached, the streets of Worcester became a chaotic scene of hand-to-hand combat. Charles II found himself in the midst of the turmoil, desperately trying to rally his men against the onslaught of Cromwell’s forces.

By late in the day, it was clear that the Battle of Worcester was lost and with it, the Royalist cause. All that was left was to preserve the life of the King at all costs. With the majority of Cromwell’s New Model Army now positioned inside the city walls and controlling three of the four city gates, it was not an easy feat for Charles II to elude capture. The most ardent followers of Charles II launched a desperate last stand near the town hall, buying him precious time to escape. As the sun began to set, Charles threw off his armor and begged his friend, Lieutenant-General Henry Wilmot, 1st Earl of Rochester, to meet him outside St. Martin’s Gate with fresh horses, if it were possible. Charles II made a daring escape through the back door of his lodgings and dashed the few yards to the gate while Cromwell’s men entered at the front.

Despite his strong desire to return to the city and continue the fight, Charles II knew that his survival depended on evading capture. With a heavy heart, he rode northward with Lord Wilmot, his surviving officers, and a few hundred men, desperate to regroup and strategize his next move. As Cromwell’s men closed in on his trail, Charles II made the difficult decision to break away from the main body of evacuees with only a handful of his most trusted advisers and loyal supporters. Charles II was aware that time was of the essence, and he needed to move quickly and quietly to avoid detection.

Charles II wanted to race for London, hoping to board a ship and set sail for France or Spain before news of his defeat had reached London. However, London was far off, and the Earl of Derby suggested that the King make for Brewood, a heavily Catholic area of Shropshire where Lord Derby had recently found shelter at an old hunting lodge called Boscobel after his defeat at Wigan. Among those still with the King was Charles Giffard, the owner of Boscobel. Giffard suggested that the exhausted king might find a more suitable and elusive refuge at Whiteladies, an old priory owned by his family, nestled in the woods near Boscobel.

Guided by Derby and a local man named Francis Yates, Charles II and his comrades rode through the night, speaking French to avoid detection, until they reached Whiteladies, fifty miles north of Worcester, at three in the morning. It was here that Charles II narrowly escaped seizure numerous times, including one famous incident where he hid from a Parliamentarian patrol in an oak tree on the grounds of Boscobel House.

“The Proscribed Royalist, 1651” by John Everett Millais from 1853, depicting a fleeing Royalist after the Battle of Worcester being hidden within the trunk of a tree by a young Puritan woman, a reference to a famous incident in which Charles II himself hid in an oak tree to escape from his pursuers.

Charles II was a noticeable man standing at six feet two with dark features and a mane of raven curls. A reward of £1000 was offered for his capture, with a sentence of death for anyone caught aiding him. Lord Wilmot stayed with Charles II during his six weeks on the run. Despite the dangers, Charles II and Lord Wilmot evaded capture time after time, riding right under the noses of their pursuers. After six weeks of hardships, disguises, traveling on foot, hiding in safe houses, and a failed attempt to get out of the country at Bristol, Charles II and Lord Wilmot finally managed to escape England via Shoreham to Fécamp in France. It would be nine long years of exile residing in various European countries before Charles II would return to England, after the death of Oliver Cromwell, to reclaim the throne.

Charles II’s narrow escape from the battlefield and desperate six-week odyssey to reach safety in France, came to be known as the Royal Miracle, because of the numerous times he so narrowly dodged discovery and capture. The experience of being a fugitive was formative for him, shaping his understanding of the common people in a way no other King of England had ever experienced. After the Restoration, Charles II frequently told the story of those harrowing six weeks for the next twenty-five years of his life.

By nightfall on September 3, 1651, the Battle of Worcester had come to a bloody end. The victorious Parliamentarians had suffered minimal losses of only 200 soldiers, while the Royalist defenders had been decimated, with 3,000 killed and a staggering 7,000 to 10,000 captured. The streets of Worcester, “the faithful city,” were filled with the bodies of the fallen, both men and horses. The gutters ran with blood, creating a scene of unimaginable horror and devastation. The English Royalists captives were conscripted into the New Model Army and sent to Ireland for further service, while the Scottish survivors faced a more uncertain fate.

At nearby Kidderminster, Puritan minister Richard Baxter was roused from his bed by a troop of Royalist cavalry fleeing pell-mell through the town. “Till midnight the bullets flying towards my door and windows, and the sorrowful fugitives hastening for their lives, did tell me the calamitousness of war,” he remembered. Some of the fugitives were so exhausted that they fell asleep in the fields outside Worcester, where several of them were robbed and cudgeled to death by looters.

Oliver Cromwell, never one for mincing words, called the battle “as stiff a contest as ever I have seen.” Retiring to the aptly named King’s Head Inn at Aylesbury, he announced the stunning victory to Parliament, sending a famous letter to William Lenthall, Speaker of the House of Commons. “The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts,” Cromwell wrote. “It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.” He added a gracious and uncharacteristic postscript. Although formerly contemptuous of militia forces, he recognized the importance of their stand at Red Hill. “Your new raised forces,” he advised Parliament, “did perform singular good service, for which they deserve a very high estimation and acknowledgement.” In faraway New England, an English Anglican minister with Puritan leanings who supported the Parliamentarians during the English Civil Wars, Hugh Peter, also acknowledged the humble militia. “When their wives and children should ask them where they had been and what news,” preached Peter, “they should say they had been at Worcester, where England’s sorrows began, and where they were happily ended.”

The battle of Worcester, the final battle of the English Civil Wars, destroyed the hopes of the Royalists regaining power by military force. Charles II was forced into exile and the long and bitter war was over, appropriately ending where it had begun. The Battle of Worcester was Cromwell’s last great victory in battle, and it secured his dominant position, political as well as military, contributing to his appointment in 1653 as Lord Protector, and paving the way for the establishment of the Commonwealth.

The thousands of Scottish prisoners from the Battle of Worcester “were “driven like cattle” to London. As one witness described the convoy, “all of them [were] strip[ped], many of them cut, some without stockings or shoes and scarce so much left upon them as to cover their nakedness, eating peas and handfuls of straw in their hands which they had pulled upon the fields as they passed.” At temporary prison camps in London and other cities, many of the Scottish prisoners from Worcester died of starvation, disease, and infection, as Parliament debated what to do with the defeated Scottish multitudes.

While the Scottish prisoners of war were dying at a disturbing frequency, Stephen P. Carlson, in the Scots of Hammersmith, reported, “The disposition of such a large number of prisoners presented the English authorities with a dilemma: to maintain them as prisoners would prove costly, and to release them could prove dangerous to the security of the Commonwealth.” A committee appointed by the English governing body, the Council of State, reached a resolution to equally divide one thousand of the Scottish prisoners, 500 of the prisoners were sent to work in the coal mines of Durham and Northumberland and the other half of the prisoners were utilized to drain the fens in East Anglia, a southeast region of England.

Additionally, Oliver Cromwell and the Council of State made the unsettling yet pragmatic decision to sell the remaining 6,000 to 8,000 Scottish prisoners that were deemed “well and sound, and free from wounds,” into forced servitude overseas: 1,500 men were shipped out to the gold mines of Guinea, the majority of the Scottish captives were sent to labor on the plantations in Bermuda, Cuba, Jamica, Haiti, Barbados, and Virginia, and the remaining 900 men were bound for New England. However, the Scottish prisoners continued to perish at an alarming rate of 30 to 100 men a day until the transport ships began to depart from London.

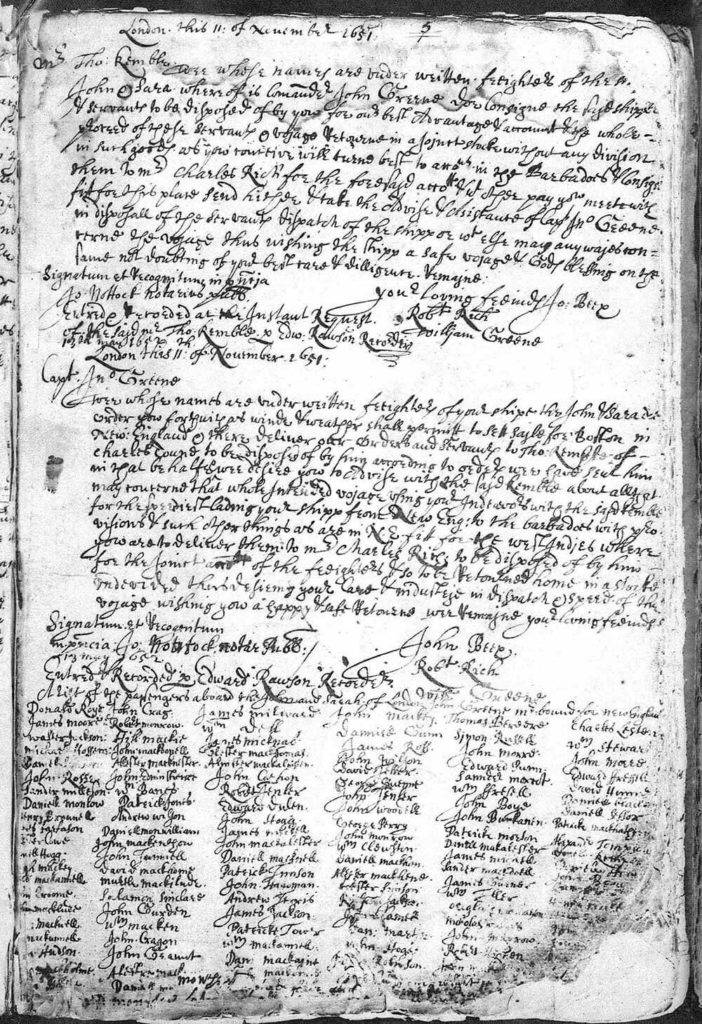

On November 11, 1651, the ketch “John and Sara” embarked on a treacherous transatlantic voyage from Gravesend, England to New England. Laden with a valuable cargo of 272 Scottish survivors of the Battle of Worcester, the two-masted merchant vessel set sail with its human cargo fettered together and chained in the dark hold below deck. The freighters of the “John and Sara”, who signed their ship’s manifest as “your loving friends”, described the Scots as “servants to be disposed of”. Puritan minister John Cotton of the Massachusetts Bay Colony wrote to Oliver Cromwell, assuring him that these men were not being sold into perpetual servitude, but rather for a term of 6 to 8 years. In 1651, the price of passage across the Atlantic was a mere £3, but the profit for the freighters was substantial, as they sold each healthy Scottish man for around £30.

The journey across the Atlantic was fraught with danger, as the prisoners of war endured cramped and unsanitary conditions, harsh weather, and uncertainty about their futures in the New World. Among the shackled was a Scotsmen from Midlothian, eighteen-year-old John Cragin, my ninth great-grandfather through my maternal grandmother.

A facsimile of the original list of human cargo aboard the “John and Sara”. Courtesy of the George Sawin Stewart Collection, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

An outbreak of smallpox on the ship threatened to take John Cragin’s life, but against all odds, he managed to overcome the deadly disease. After enduring 105 days at sea, the “John and Sara” finally arrived in Charleston, Massachusetts on February 24, 1652. John Cragin, along with his fellow Scottish prisoners of war, found themselves bound to a new land, anxious of what awaited them in this unfamiliar territory.

Sold as indentured servants as punishment for their rebellion against Oliver Cromwell, the Scottish prisoners of war were consigned to Thomas Kemble, a major player in the shipping industry in Massachusetts. Kemble, a well-off merchant who imported household goods and necessities, also exported lumber to England from his New England mills. With orders from Cromwell to deal with the Scottish prisoners as he saw fit, Kemble sold them to the highest bidders. Seventeen of the Scots were sold to a sawmill near Berwick, Maine, while some were sent to New Hampshire sawmills and others to work on farms across New England. Most of the men, including John, were sold to Saugus Iron Works in Hammersmith, Massachusetts.

Saugus Iron Works, located ten miles northeast of downtown Boston, was a marvel of technological achievement in its time. Built in 1646, it was the first ironworks in North America and played a vital role in the development of the colonies. Situated near ore deposits and the Saugus River, the ironworks utilized waterpower to operate a variety of machinery including a blast furnace, reverberatory furnace, trip-hammer forge, and rolling and slitting mills. One of the most important products of Saugus Iron Works was nails, a crucial commodity for the rapidly expanding settlements in the wilderness. The ironworkers at Saugus milled strips of wrought iron, slit them into pieces, and sold them to customers who would then shape the nails. This process not only provided a valuable product but also fostered the growth of a community known as Hammersmith. Though Saugus Iron Works was closed by 1675, its legacy lives on as a testament to the ingenuity and industry of early American settlers.

The Scottish servants arrived at the Saugus Iron Works in Hammersmith, from Boston by boat. Their initial payments for food were meticulously recorded in the record books of John Giffard, the agent for the undertakers of the iron works, in March of 1652. It was clear from the records that these Scots were in poor health, with payments also being made for medicine and medical examinations. Tragically, one death was recorded among them.

Despite their hardships, the Scots worked diligently at the iron works, taking on various roles such as wood cutters, colliers (who produced charcoal for the iron works), and unskilled laborers, such as attending to the cattle at Hammersmith. A fortunate few were taught skilled trades such as smithing, sawyers, finers, hammerman, and carpentry. They were provided with company housing and the essentials needed to live and work.

At the Saugus Iron Works, the Scottish indentured servants toiled tirelessly in hot, dangerous environments under the watchful eyes of their Puritan masters. Many of these Scotsmen might have seen their indentures as a stroke of luck, as it meant they avoided the harsh conditions of prison back in England. However, this stroke of luck came with a heavy price — they were thousands of miles away from their families and their homeland. As prisoners of war, the Scots were unable to bring their loved ones with them to the New World. They were also faced with the challenge of being outsiders in a society dominated by Puritans with different religious beliefs. Despite these obstacles, the Scottish prisoners of war eventually worked off their indentures, but for many, the journey back home to Scotland was never realized. The majority of the Scots chose to stay in New England, marrying and starting new families, assimilating into Puritan society.

John Cragin longed for the day when he could once again taste freedom and escape the bonds of indentured servitude. For nine long years, John Cragin labored at Saugus Iron Works to repay all his debts of transportation from England to Massachusetts, food, shelter, and medical care. After nine years of exertion, John Cragin was awarded his freedom and a grant of land in Woburn, Massachusetts.

While John Cragin endeavored at repaying his indenture at Saugus Iron Works in Hammersmith, Sarah Dawes worked as a servant for John Wyman, one of the largest landholders in Woburn, Massachusetts. Also, working for John Wyman as a servant was Daniel Mecrist. Sarah Dawes, a woman burdened by the weight of her mistakes, stood in court on April 7, 1657, visibly pregnant, alongside Daniel Mecrist. They were convicted of the sin of fornication and faced a punishment of twelve stripes. Luckily for Sarah, a member of the community, Francis Kendall intervened, and paid her fine of 40 shillings. Despite her reprieve, Sarah’s life continued to be marred by scandal. Daniel Mecrist, unable to marry her due to his existing marriage in Scotland, found himself in trouble with the law once more on October 3, 1659, when Sarah Dawes was obviously expecting her second child with him. This time, they were both sentenced to be publicly whipped twenty stripes each, a harsh reminder of their transgressions.

Though their courtship remains shrouded in mystery, John Cragin married Sarah Dawes on November 4, 1661, in Woburn, Massachusetts. John Cragin embraced Sarah’s children, Mary and Benoni Mecrist, as his own, raising them with unconditional love and care. Together, John and Sarah went on to have eight children of their own. Abigail, born on August 4, 1662, married Captain John Knight and they had eleven children. Sarah, born on August 10, 1664, married Francis Nurse, Jr., and they also had eleven children. Notably, Francis Nurse, Jr. was the son of Rebecca Towne Nurse, who was hung as a witch in 1692 in Salem, Massachusetts.

Elizabeth Cragin was welcomed into the world on August 3, 1666. She grew up to marry John Shepard, Jr. and together they had three children. Mercy Cragin, my eighth great-grandmother, was born on March 25, 1669. She married Thomas Skelton, a descendant of the Reverend Samuel Skelton of Salem, Massachusetts, and they had five children. Ann Cragin arrived on August 6, 1673, followed by John Cragin, Jr. on September 19, 1677. John Jr. married Deborah Skelton and they had three children of their own. Sadly, the twins Rachel and Leah were born on March 14, 1680, but tragically passed away just four days later.

John Cragin never again viewed the rolling hills of his homeland in Scotland. From the depths of war, captivity, and indenture, he emerged as a free man, creating a life hopefully filled with happiness, love, and prosperity. On January 27, 1708, John Cragin passed away in Woburn, Massachusetts. His tale of resilience and survival in the face of unimaginable hardship is a testament to the human spirit. John Cragin’s story is a reminder that through courage and perseverance, we can each overcome even the most daunting challenges. His strength and determination in forging a new life in a foreign land paved the way for generations of his descendants, including me.

Sources

Atkin, Malcolm. Worcester, 1651. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Books, 2004.

Boyer III, Carl. Ship Passenger Lists: National and New England (1600-1825). Newhall, California, Published by Carl Boyer III, 1977, Pages 164-171.

Chadler, Charles Henry. The History of New Ipswich, New Hampshire, 1735-1914: With Genealogical Records of the Principal Families. Fitchburg, Massachusetts, Sentinel Printing Company, 1914.

Dobson, David. Directory of Scots Banished to the American Plantations, 1650-1775. Baltimore, Maryland, Genealogical Publishing Company, 1983.

“Massachusetts, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1626-2001,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FHXN-1PY : March 17, 2024), John Cragin, October 27, 1708; citing Will, Woburn, Essex, Massachusetts, United States, town clerk offices, Massachusetts; FHL microfilm 864,290.

Rapaport, Diane. Scots for Sale, The Fate of the Scottish Prisoners in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts, New England Ancestors. Boston, Massachusetts, New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2009.

Leave a reply to Tammy Loftis Cancel reply