A Swamp Fox Soldier, Frontier Scout, and Witness to the Making of America

(1760 – 1864)

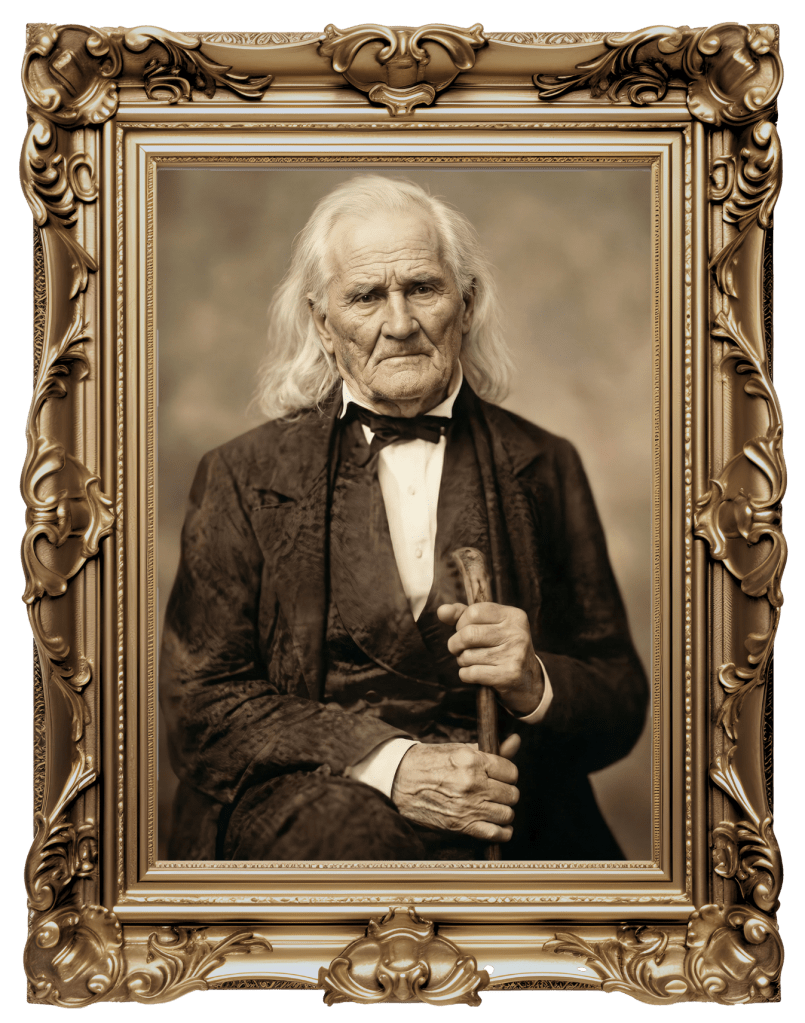

A digitally restored tintype portrait of Thomas Mills, captured between 1850 and 1864.

This refined image preserves the quiet dignity and weathered resolve of a man whose life bridged the colonial world and the young American republic.

Cleaned and clarified by me from its original tintype form, it offers a rare and intimate glimpse into the face of a Revolutionary-era survivor living deep into the nation’s turbulent mid-19th century.

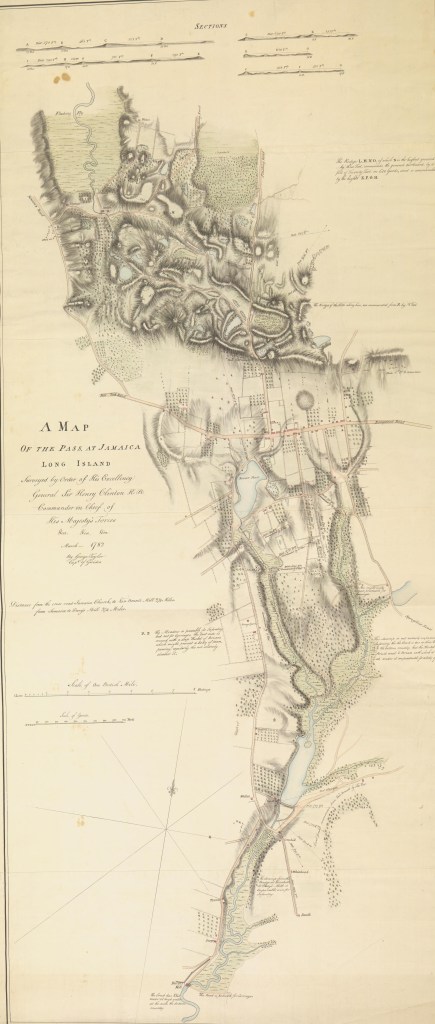

Thomas C. Mills entered the world not as a citizen of the United States, but as a subject of King George III—born on September 29, 1760, in Jamaica, Long Island, an ancient settlement first carved into being by Dutch colonists. Jamaica—originally Rustdorp, the “Rest-Town” founded under Governor Pieter Stuyvesant—was a crossroads of cultures: Native lands, Dutch ambitions, and English colonial reach. When the English wrested control of New Netherland in 1664, the name Rustdorp quietly vanished, and by 1680 the broad region had taken on the name Jamaica. By the time Thomas was born to Hope Mills III and Abigail Foster, the village lay within the restless hum of pre-Revolutionary life, a place already layered with complex histories and competing sovereignties.

Yet it was not the settled rhythms of Long Island that would shape the contours of Thomas’s destiny, but rather the raw, untamed frontier of the American South and West.

This meticulously drawn military map captures one of the critical landscape corridors of Revolutionary-era Long Island, charted at a moment when British command sought to secure strategic routes and defenses. Rendered with precision and purpose, it stands as both a geographic document and a vivid artifact of the shifting tides of the American Revolution.

A Boy of Twelve in a Land About to Ignite

When Thomas Mills was barely twelve years old, he traveled south with his father and elder brother, Amos, to South Carolina, just as colonial tension was hardening into rebellion. It was a harsh, unforgiving land in the 1770s—but one that forged men quickly. Within a few short years, the boy who had been born on the edge of the Atlantic had become a young soldier in a world turned violently upside down.

By age sixteen, Thomas Mills had joined one of the most daring and unconventional fighting forces of the Revolution: the troops of Lieutenant Colonel Francis Marion, the legendary “Swamp Fox.” Francis Marion’s men fought not in open fields but in the tangled recesses of the Lowcountry swamps, using stealth, mobility, and intimate knowledge of the land to terrorize British outposts and sever supply lines. Their fights were not grand battles but sudden flashes of gunfire in cypress shadows—hit, run, and disappear.

It was the British commander Banastre Tarleton, humiliated after a grueling 26-mile chase through treacherous marshes, who famously spat out that the Devil himself could not catch Marion. From that moment, “Swamp Fox” became a moniker of myth—and Thomas Mills, one of his hard-ridden fighters, earned in death the inscription now chiseled into his military grave marker: “Swamp Fox Soldier.”

This finely detailed illustration captures the enduring mystique of Francis Marion—“The Swamp Fox”—the Revolutionary War commander whose mastery of guerrilla tactics helped reshape the Southern campaign.

Crafted by two of the era’s most skilled engravers, the print preserves both the romance and the resolve that have long defined Francis Marion’s place in American memory.

War, Capture, Survival, and Escape

The Revolution put Thomas Mills at the knife-edge of danger. Between 1776 and 1779, he served with Francis Marion and later with the 2nd South Carolina Regiment, living the brutal improvisational warfare that defined the Southern Campaign.

In his later years, Thomas Mills often reflected on the many hardships and small triumphs that marked his time in service, but one memory glowed with particular pride. He recounted that, during the war, he had once been granted the rare and unexpected honor of shaving with a razor that had personally belonged to General George Washington himself. It was a fleeting moment—simple in action yet immense in symbolic weight. For Thomas Mills, that razor was not merely a tool; it was a tangible connection to the commander whose leadership helped shape a nation. Long after muskets had fallen silent and the republic had taken root, he cherished that memory as one of the most extraordinary privileges of his youth, a story he carried like a medal earned not in battle, but in proximity to history.

In 1780–1781, while scouting along the Obion River in what is now Tennessee, Thomas Mills was captured by members of the Chickasaw Nation. His captivity unfolded in the borderlands of cultures and sovereignties—a reminder that the frontier was not empty but deeply inhabited, contested, and fiercely defended by Indigenous peoples.

Against staggering odds, Thomas Mills escaped, fleeing northward into the wilds of Kentucky and the Ohio Valley. Alone, unarmed, and hunted, he crossed a landscape that would have been largely trackless, inhabited only by Native nations and a scattering of European scouts.

His survival was no small feat; it marked the beginning of years spent as a scout and woodsman, honing the skills that made him invaluable on the frontier.

Pioneer of Kentucky and the Ohio River Valley

By 1783, Thomas Mills had drifted into Kentucky—then a raw, dangerous borderland—where he hunted with Simon Kenton, one of the most storied pioneers of the Ohio Valley. As a scout he also met Daniel Boone, Andrew Jackson, and other figures on the edge of American expansion.

Thomas Mills lived the archetype of the frontier scout: “For several years he never once slept in a house.”

He traversed the unknown territories of present-day Ohio and Indiana before a single white settlement existed there. In fact, Thomas Mills arrived in the West in 1785, when there was not yet a soul in Cincinnati; it would be three more years before the first settlement appeared.

He helped petition for the creation of early Kentucky settlements, including Washington and Limestone (later Maysville) in 1786, giving shape to the first towns of the region. During these years, the thin lines between survival and death were constant companions. He witnessed Native raids on settler encampments and carried lifelong memories—some honorable, others traumatic—of a world in which cultural collisions were often violent and devastating.

The frontier was a place of both tragedy and transformation, and Thomas Mills lived at the center of that turbulence.

A Lost Family, a Fallen Scrap of Cloth, and a Reunion Beyond Belief

Communication with the East was nearly impossible. For nine years, Thomas Mills heard nothing of his parents. Then, in an extraordinary twist of fate, he happened upon a scrap of cloth in the road near the settlement of Columbia, just above Cincinnati. Assuming it belonged to a nearby cabin’s inhabitants, he returned it—only to discover, upon opening the cabin door, that he had stepped into his own father’s home. Hope Mills III had migrated west scarcely months earlier.

It was a reunion that defied probability—a moment of grace in a world of hardship.

Family Life and Service to a Growing Nation

Thomas Mills married Lydia Wilson in Paris, Kentucky, on May 16, 1786, and together they had several children before her death in 1805. He remarried the following year, taking Lydia Cachel as his wife in Lebanon, Ohio, and ultimately fathered a total of thirteen children, twelve of whom lived to adulthood.

His movements across Kentucky and Ohio—from Clermont County to Cheviot and Mill Creek—trace the slow westward creep of American settlement.

His service to the new nation did not end with the Revolution. From 1783–1785, he served as a scout. From 1786–1799, he served with the Kentucky militia, often called the Corn Stalk Militia, a force of mounted riflemen who patrolled frontier settlements. He fought again in the War of 1812, defending lands he had helped settle.

While still living on the Kentucky frontier, Thomas Mills served his community in a role that was both humble and vital: he was a runner for the Bracken Baptist Association—first for the Stone Lick Church in Mason County in 1801, and again in 1803 for the congregation at Indian Run.

In an era before newspapers reliably reached the wilderness and when settlements lay scattered across miles of rugged, often perilous terrain, runners were lifelines. Thomas Mills traversed distances carrying letters, messages, and crucial information to isolated families—news of political developments, matters of church governance, warnings of potential raids by Indigenous warriors, and any intelligence deemed essential for survival and preparedness. His work demanded endurance, courage, and an unshakeable sense of duty. In these early years, long before railroads or telegraphs bound the nation together, Thomas Mills helped knit a fragile frontier community through the simple but profoundly important act of keeping its people informed and connected.

A Final Migration Westward

Around 1810, long before Illinois became a state, Thomas Mills migrated into the Illinois Territory, again pushing ahead of the growing nation. Five generations of his descendants would live within ten miles of where he settled in Illinois.

In 1835, in his seventies, he moved once more—this time to Boone County, Kentucky, to spend his final years on the quieter side of a life once defined by danger.

A Century of Witness

Thomas Mills lived to the astonishing age of 104. His life formed one of the longest personal bridges in American history—from colonies to Civil War. He cast his first vote for George Washington, and voted in every presidential election through Stephen A. Douglas in 1860, having participated in all eighteen presidential elections held since the U.S. Constitution’s ratification.

Yet the anguishing realities of the Civil War were mercifully kept from him. He had predicted such a conflict decades earlier, and his family shielded the old pioneer from the scenes of disunion and bloodshed that ravaged the country he had watched come into being.

When he died, he was described as one of the very last living links to the pioneers who knew Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton. His passing was seen as the closing of a chapter— “The great tie that has linked the West with its first founders is broken.”

Legacy

Thomas Mills was a man shaped by the terror, promise, brutality, and possibility of the American frontier. He was a soldier in the Revolution, a prisoner who escaped into wilderness, a scout of the early West, a hunter with Simon Kenton, a petitioner of early Kentucky towns, a veteran of 1812, a patriarch of thirteen children, and a voter whose political life spanned from Washington’s presidency to the age of Lincoln.

He was also a man of his time—carrying deep suspicion and resentment toward Native peoples, shaped by the violent encounters and tragedies he witnessed. His prejudices, while historically common among frontier families, remain part of the sobering truth of America’s expansion, a reminder of the immense cultural collisions that defined the era.

The back of his gravestone bears the words: “Swamp Fox Soldier – Kentucky Corn Stalk Militia.”

But his true monument is larger: a life that spanned the birth of a nation, that weathered every hazard the frontier could hurl, and that left descendants whose lives still unfold in the lands he helped settle.

In the long arc of American history, Thomas C. Mills, my 5th great-grandfather, stands not merely as an ancestor, but as a living testament to the peril, perseverance, and complexity of the country’s earliest generations—a man who walked out of the colonial world and lived long enough to see the nation fray at its seams.

Thomas Mills was a man who saw the American story from the very beginning.

Leave a comment