In his sweeping, four-volume masterpiece Conceived in Liberty, the twentieth-century economist and libertarian historian Murray Rothbard painted Anne Hutchinson in blazing colors: a fierce individualist, a radiant threat to what he saw as the “despotic Puritanical theocracy of Massachusetts Bay.” Murray Rothbard recognized in her a mind that refused to bow, a woman whose conscience burned too brightly to be dimmed by the stifling strictures of a fledgling colony.

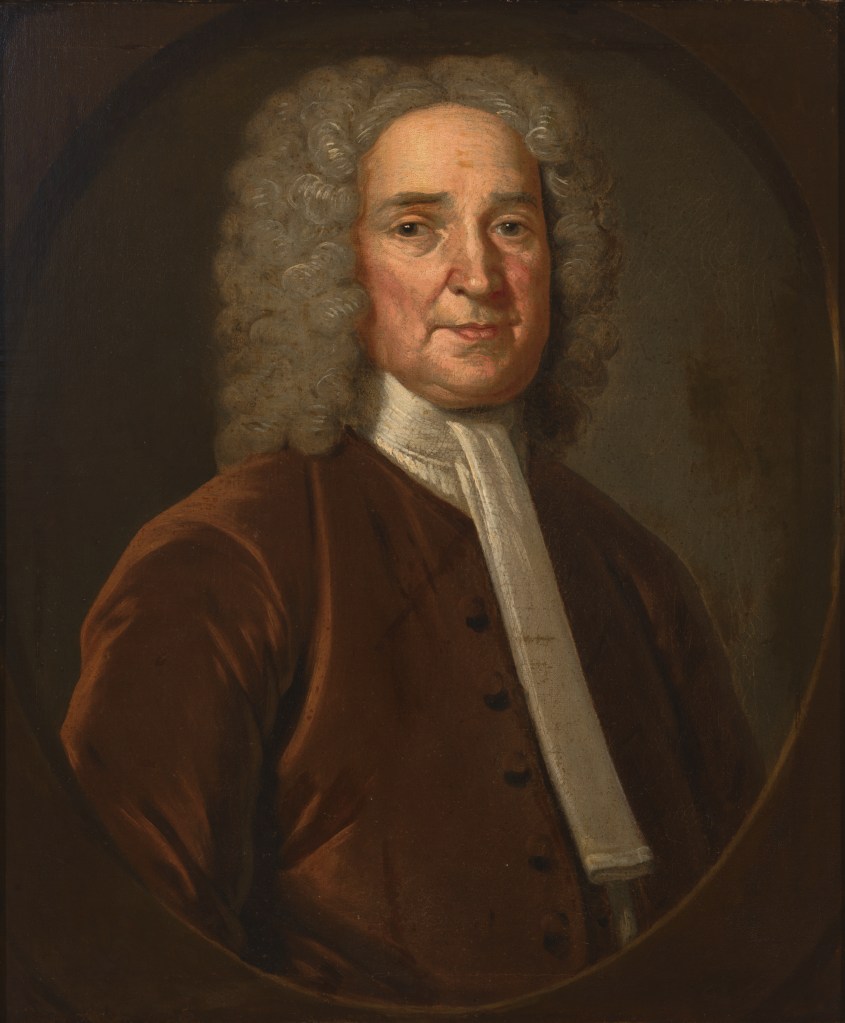

Her most formidable opponent, John Winthrop—the 2nd, 6th, 9th, and 12th governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—saw something very different. To him, she was a subversive spark in his carefully tended New Jerusalem: “a hell-spawned agent of destructive anarchy,” a woman “of haughty and fierce carriage, a nimble wit and active spirit, a very voluble tongue, more bold than a man.” Few men reveal their fears so plainly as when they attempt to silence a woman who will not bend.

Time, however, has proved the more generous judge. In the Massachusetts State House today stands a monument hailing her as a “courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration.” Murray Rothbard’s vision and the Commonwealth’s commemoration—though separated by centuries—converge in their recognition of the extraordinary legacy of a woman who refused to shrink into the shadows. In the crucible of seventeenth-century New England, Anne Hutchinson became the preeminent female voice for freedom of conscience, a role for which she paid with exile, and ultimately, with her life.

The Antinomian Upheaval — How Her Voice Became a Storm

Anne Hutchinson’s story coils itself tightly around the theological and cultural phenomenon known as the Antinomian Controversy, or the “free grace” crisis, which roiled Massachusetts from 1636 to 1638. The name “antinomian”—literally “against the law”—was not an identity her followers claimed, but a slur hurled by the Puritan establishment against a movement that dared to emphasize the primacy of personal revelation, conscience, and divine grace over the rigid formulas of clerical authority.

Anne Hutchinson lived centuries ahead of her age. In a world that confined women to the hearth, barred them from owning property, restricted their movements, and denied them a say in civic life, she rose to challenge every one of those boundaries—and many more—with a courage that still reverberates through history. In a society where women were expected to remain silent spectators in all matters of theology and governance, Anne Hutchinson did the unthinkable: she spoke. Her charisma was undeniable; her intellect, formidable; her spiritual insight, electrifying. Historian Emery Battis, in Saints and Sectaries, described her with an admiration that even time cannot dull:

“Gifted with a magnetism which is imparted to few, she had, until the hour of her fall, warm adherents far outnumbering her enemies, and it was only by dint of skillful maneuvering that the authorities were able to loosen her hold on the community.”

The Puritan clergy insisted that salvation understanding came from Sola Scriptura—Scripture alone. Anne Hutchinson and her “free grace” allies agreed in principle, but insisted that God continued to speak to the individual heart through what she called the inner light. As she explained with disarming clarity:

“Laws, commands, rules, and edicts are for those who have not the light which makes plain the pathway. He who has God’s grace in his heart cannot go astray.”

That single idea—that God could speak directly to the individual soul, without clerical permission—was enough to shake the colony to its foundations.

The Sources of Her Defiance — A Seed Planted in England

Born in 1591 in Alford, Lincolnshire, England, Anne was the daughter of Bridget Dryden and Francis Marbury, an outspoken Anglican minister and gifted schoolmaster who passed on to her both intellect and conviction. She later married her childhood companion, William Hutchinson, beginning a partnership that would follow them across an ocean and into the heart of a colonial storm.

Anne Hutchinson grew up amidst the great convulsions of the Protestant Reformation. The England of her youth strained under competing visions of authority—divine, royal, and ecclesiastical. In this volatile world, Anne found her spiritual anchor in the brilliant, controversial preacher John Cotton, whose teachings emphasized an intimate relationship with God. When John Cotton fled to New England in 1633, Anne followed three years later, arriving in a colony primed for revival and ripe for conflict.

In Boston, she balanced her roles with superhuman vigor: devoted mother of fifteen children, skilled midwife, tireless caregiver, and theological thinker capable of out-debating seasoned ministers. Her energy was prodigious; her resolve, granite.

A Colony Divided — Clerical Fury and Deep-Rooted Misogyny

Anne Hutchinson’s weekly gatherings—conventicles—drew dozens of women, and soon, scores of men, including civil leaders and well-respected colonists. These meetings did more than interpret sermons; they questioned them. They did more than encourage piety; they encouraged critical thought. In doing so, they pried open a crack in the wall of Puritan orthodoxy through which a flood of new ideas poured.

Boston increasingly leaned toward her theology, while the countryside clung to the rigid Puritan establishment. The lines were drawn not only between doctrines, but between genders, political factions, and visions of society.

By 1636, her allies—including John Cotton, the fiery Reverend John Wheelwright, and sitting governor Henry Vane—came under ferocious attack. Reverend John Wheelwright was banished for “contempt & sedition.” Massachusetts governor Henry Vane was voted out, replaced by John Winthrop, who coveted a return to orthodox order and saw Anne Hutchinson as a destabilizing force.

Rumors of Anne Hutchinson’s sexual impropriety—a frequent weapon used against outspoken women—swirled baselessly. As pressure mounted, Anne Hutchinson refused to recant or retreat.

The Trial — A Battle of Wits Against a Wall of Power

In November 1637, Governor John Winthrop orchestrated her civil trial, charging her with troubling the peace of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and stepping out of her “proper place.” Her true crime, however, was neither sedition nor heresy: it was audacity. She had dared to learn, dared to question, dared to teach.

Governor John Winthrop scolded:

“You have maintained a meeting in your house that is condemned… nor fitting for your sex.”

To which Anne Hutchinson answered with the brilliance and bite that made her unforgettable:

“Do you think it not lawful for me to teach women, and why do you call me to teach the court?”

On the trial’s first day, she outmaneuvered the magistrates with such deft intellect that even her critics conceded she bested them. Biographer Richard Morris noted she “outfenced the magistrates in a battle of wits.” Eve LaPlante observed that her success came not from pride, but from an intimacy with God that gave her unshakeable confidence.

But on the second day, in a moment of prophetic conviction, she declared:

“Take heed how you proceed against me—for God will ruin you and your posterity and this whole state.”

Her opponents seized upon this as proof of sedition. She was convicted, denounced as “a woman not fit for our society,” and banished.

Four months later, a church court formally excommunicated her. Reverend Thomas Shepard cast her out with chilling severity:

“I deliver you up to Satan… as a Leper to withdraw yourself out of the Congregation.”

Exile, Resolve, and a Tragic End

In April 1638, Anne Hutchinson, her husband William, and their children journeyed on foot through snow and hardship to Providence, Rhode Island, the refuge founded in 1636 by Reverend Roger Williams for the persecuted. Roger Williams, too, had been cast out by the Puritan magistrates of Massachusetts Bay. Yet from his exile emerged a refuge unlike any other in the Western world. Roger Williams championed what he called “liberty of conscience,” and through his vision, Rhode Island became the first government to guarantee full religious freedom in its founding charter—a radical promise centuries ahead of its time.

Originally a Puritan minister, Roger Williams later embraced Baptist beliefs for a brief period, and in 1638 he established the First Baptist Church in America in Providence, the earliest Baptist congregation on the continent. His unwavering devotion to freedom of belief would shape the soul of Rhode Island and echo across the future United States.

Anne Hutchinson and her family later moved to Aquidneck Island, helping to establish Portsmouth alongside many of the Antinomian exiles. The name of Aquidneck Island which was changed in 1644 to Rhode Island. While there William Hutchinson became the first governor of Rhode Island. In the years that followed her banishment, Anne Hutchinson’s fortunes collapsed with heartbreaking speed. Her husband William died in 1642; her once-galvanizing religious influence diminished; and the ever-encroaching Massachusetts Bay leadership threatened to swallow the fragile Rhode Island settlements she had helped inspire. Disillusioned and weary of conflict, Anne Hutchinson sought a more distant refuge. In 1642 she moved with eight of her younger children to the Dutch colony of New Netherland, hoping to find peace beyond the reach of Puritan hostility.

But the frontier was no sanctuary. By late summer of 1643, her homestead—near present-day Pelham Bay, New York—lay squarely in the path of a brutal conflict between Dutch colonists and Indigenous nations resisting displacement. Anne Hutchinson may have believed her earlier warm relations with the Narragansetts would shield her from violence, but fate intervened with tragic force. Members of the Siwanoy tribe raided her home, and Anne, along with seven of her children, were killed with horrific brutality. Their dwelling and bodies set ablaze in the aftermath—a tragedy not of her making but of the brutal geopolitics of the time.

Only her nine-year-old daughter Susanna Hutchinson survived, adopted into the Siwanoy tribe until she was returned to the English years later.

The reaction in Massachusetts was chilling. Many of the colony’s orthodox clergy rejoiced, interpreting the massacre as divine judgment. The Reverend Peter Bulkeley spoke for the Puritan establishment when he declared, with merciless triumph, “Let her damned heresies … and the just vengeance of God, by which she perished, terrify all her seduced followers from having any more to do with her heaven.” To the ministers of the Bay, Anne Hutchinson’s death symbolized the final ruin of Antinomianism. Yet her influence proved irrepressible. Many of her followers found their spiritual home among the emerging Quaker movement, which resonated deeply with her insistence on the primacy of conscience.

Legacy — America’s First Feminist and Prophet of Liberty

Though her body perished, Anne Hutchinson’s voice has never gone silent. In the final measure of her life, Anne Hutchinson left the world as she had lived within it—unyielding, luminous, and unwilling to be anything less than fully, defiantly herself. Though the forces of her age sought to bury her under accusation, exile, and, at last, unspeakable violence, they could not bury the ideas she carried. Her spirit—unyoked from the confines of time—moved forward into the centuries that followed, shaping consciences, challenging systems, and whispering courage into the hearts of those who dared to dissent.

Her story is not merely a chapter in the annals of early New England; it is a mirror held to the soul of a nation before it knew itself. In Anne Hutchinson, we glimpse the earliest contours of American liberty, the first flashes of feminist fire, the unwavering insistence that conscience is sovereign, and the radical belief that truth belongs to everyone, not merely to the powerful.

From the hearths of Portsmouth to the halls of Providence, from the windswept shores of Aquidneck Island to the quiet inlet where her life met its tragic end, her influence stirred women to speak and men to reconsider the structures they had built. The freedoms enjoyed in Rhode Island—freedoms once unthinkable in Boston—owe much to the footsteps she left along its shores. After her arrival in Portsmouth, and throughout the remainder of the seventeenth century, women across Rhode Island publicly taught, preached, and gathered in ways unimaginable in neighboring colonies. Her example emboldened them, and the men of Rhode Island—long mindful of the tyranny she had fled—protected the freedom of women to worship and speak as their consciences dictated.

To call Anne Hutchinson, my 11th great-grandaunt, America’s first extraordinary female leader is not an embellishment but a recognition of what she was: a woman who carried within her the architecture of a more just world, long before that world existed. Her brilliance, her ferocity, her relentless devotion to the sovereignty of the soul—these are the gifts she pressed into the nation’s early clay.

In time, even Massachusetts sought to make amends with Anne Hutchinson. Acknowledging the injustice done to her, the Commonwealth commissioned renowned sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin to craft a statue portraying Anne sheltering a child beneath her robes. Dedicated in 1922, the sculpture bears the inscription “a courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration.” Today it stands in a honored alcove of the Massachusetts State House, inviting all who pass to reflect on the woman once condemned—and now celebrated—as one of the earliest champions of freedom in the New World.

In Anne Hutchinson’s memory, a tract of land near the site of her former home in New York State was later named “Anne-Hoeck’s Neck.” The nearby waterway came to be known as the Hutchinson River, and in time, a major regional thoroughfare—the Hutchinson River Parkway—was built alongside it, quietly carrying her name into the modern world.

And so, as the centuries continue their march, Anne Hutchinson endures—not as a martyr of dissent alone, but as a herald of the freedoms that would one day define a people. Murray Rothbard wrote that “the spirit of liberty she embodied” ultimately outlasted the Puritan theocracy that tried to extinguish her. In remembering Anne Hutchinson, I honor not only an ancestor, but a visionary whose courage helped light the path toward a nation still waiting to be born.

Leave a comment