Edmund Freeman II, my 11th great-grandfather, lived at the crossroads of family ambition, religious conviction, and the perilous experiment of building a new society on the edge of the Atlantic wilderness.

A World on the Move: The Pilgrims and Their Financiers

Before Edmund Freeman II ever saw the shores of New England, the stage for his life there had already been set.

In 1608, a group of English Separatists–later remembered as the Pilgrims–left England for the Netherlands. Holland offered something England did not: a degree of religious toleration. Yet that very openness worried them. They feared their children would become Dutch in language and customs, and they disliked what they saw as a worldly, liberal society. After a decade, many chose to return to England and then, in 1620, to cross the Atlantic and found Plymouth Colony.

The Pilgrims were mostly tradespeople of modest means. Crossing an ocean, hiring a ship and crew, and supplying a new settlement were all ruinously expensive. To finance their venture, they turned to investors and trading companies such as the Plymouth Company. In this early age of overseas expansion, such companies were often backed by aristocrats or groups of wealthy merchants. They provided ships and supplies, expecting to be repaid in valuable commodities: furs, timber, fish, or tobacco.

Virginia soon became profitable through tobacco. Plymouth did not. The land near the harbor was sandy, the climate too cold for tobacco, and the fur trade faced stiff competition from French and Dutch traders. As years passed, Plymouth struggled to repay its debts. Some investors abandoned their claims; others restructured the debt, making key colonists personally liable.

Among those determined creditors was a London merchant named John Beauchamp. He invested heavily in Plymouth and spent years trying to recover his money. Fortunately for him, he had a brother-in-law with both the ability and the courage to cross the ocean and take a more direct hand in his colonial investment: Edmund Freeman II.

Roots in Sussex: A Gentry Childhood

Edmund Freeman II was baptized on July 25, 1596 in Pulborough, Sussex, England, son of Edmund Freeman I and Alice Coles. He was the sixth of twelve children in a large and complex family that included four sets of twins; only three of the eight twins are known to have survived. Edmund himself was one of the few children who was not a twin.

The Freemans were well-to-do gentry. Edmund grew up in a household that enjoyed education, land, and social standing. In early-seventeenth-century England, inheritance followed a familiar pattern:

- The eldest surviving son–in this case, Edmund’s brother William–inherited the bulk of the family estate and often managed the family business. William was known as Captain Freeman, suggesting maritime or trading interests.

- The next surviving son frequently went into law; this was Edmund’s path.

- Younger sons might purchase commissions in the military, go into trade, or join the clergy.

Edmund trained as a barrister, a significant mark of education and status. The family appears to have had ties to ocean-going trade, which may have foreshadowed the Atlantic world that would later shape Edmund’s life.

The Freeman household was also well-connected. They were related to the Earl of Warwick, an important figure in early English colonization, and Edmund’s younger sister Alicia Freeman married John Beauchamp, the London merchant who became one of the chief financiers of Plymouth Colony. The Earl of Warwick served on the Council for New England, and John Beauchamp was one of the original seven financiers of Plymouth. These connections would prove decisive.

Bennet Hodsoll and a Prosperous Young Couple

Edmund’s first wife, Bennet Hodsoll, my 11th great-grandmother, came from an equally prosperous background. She was baptized on August 23, 1596 at All Saints Barking, London, daughter of John Hodsoll and Anne Maundy. Her father was a wealthy supplier to shipbuilders, owning multiple houses in London and estates south of the city. Bennet grew up amid the trappings of wealth and received a good education.

When Bennet was seventeen, her mother died, and the family moved to Cowfold, Sussex, to one of their country estates. Cowfold lay only about thirteen miles from Pulborough, where Edmund lived. The two villages likely shared a market town, and it was probably at such a market–or at a local social gathering–that Edmund and Bennet first met.

They married in Cowfold on June 17, 1617, just shy of their twenty-first birthdays. Later that year Bennet’s father died, leaving her £100 (roughly $23,624 in 2025 dollars) to be paid a year after his death. When her brothers delayed payment, Edmund sued to secure his wife’s inheritance.

In that lawsuit, a man named John Draper gave a deposition describing Edmund’s means:

“He has lands at Pulborough to the yearly value of £50 [about $11,812 in 2025 dollars], though an older man named Wexham holds £15 of that per annum for life. He also has copyhold lands at Billingshurst worth £80 per annum [about $18,899 in 2025 dollars], held for his lifetime and that of one of his children, and he is a man of good credit and estimation among his neighbors, with goods, plate, chattels, and household stuff.”

When Edmund’s father died in 1632, Edmund inherited £800 (roughly $188,990 in 2025 dollars) and a substantial portion of the family lands, from which he could draw rents. By any measure, Edmund and Bennet were comfortable, wealthy, and secure.

The couple had six children. The first two were probably born in Pulborough. Around 1621, the family moved to Billingshurst, about six miles north; by 1626, they were again associated with Pulborough. Because Pulborough and Billingshurst shared a parish and the Freemans held land in both, the children’s baptisms are recorded in both places. Their youngest child, Nathaniel, died as an infant in 1629, and Bennet herself died in Pulborough on April 12, 1632, at only 36 years old, leaving Edmund with five surviving children between the ages of six and thirteen.

Within a year, their daughter little Bennett also died at age eleven. Edmund, though supported by servants, now faced the demanding task of raising four children on his own.

A Second Marriage and Deepening Convictions

Edmund did not remain a widower long. On August 10, 1632, four months after Bennet’s death, he remarried in Shipley, Sussex. The best evidence suggests that his second wife was Elizabeth Raymer, three years his junior. When they married, Edmund was 36 and Elizabeth 33. She had one daughter from a previous marriage, Mary, born in London around 1632.

Edmund and Elizabeth were deeply religious Puritans–and, more specifically, appear to have sympathized with Anabaptist beliefs. Like other Puritans, they rejected the ceremonial “pageantry” of the Church of England, which they felt too closely resembled Roman Catholic practice. They favored simple worship, Scripture-centered preaching, and wide literacy so everyone could read the Bible.

As Anabaptist-leaning Puritans, they went further:

- Rejecting infant baptism,

- Questioning the tight union of church and state,

- And leaning toward a radical idea for their time–that civil government should not enforce religious conformity.

These convictions, combined with growing persecution of Puritans in England, pushed them toward emigration. Their family ties added a practical motive: Edmund’s brother-in-law John Beauchamp was struggling to recover his investment in Plymouth Colony. Having Edmund on the ground in New England as an agent, mediator, and trusted relative would be very useful.

Crossing the Atlantic: The Abigail, 1635

In June 1635, Edmund, his second wife, and four of his surviving children made the most consequential decision of their lives. On June 4, 1635, they boarded the ship The Abigail at Plymouth, Devon, joining about 200 passengers bound for New England.

On the passenger list, Edmund appears with the rank of “Gentleman.” In English society this indicated membership in the landed gentry–below the nobility but above commoners–and was a marker of birth, education, and social standing. This status followed him across the Atlantic; in Plymouth Colony records, his name is often prefaced by “Mr.”, an honorific reserved for very few.

The crossing was dangerous. A smallpox outbreak–every passenger’s worst fear–swept the ship. A number of travelers died, but the Freeman family survived. After roughly ten weeks at sea, The Abigail dropped anchor in Boston Harbor on October 8, 1635.

Edmund, then 39, Elizabeth, 35, and the children began their new life in a land that was still little more than a tenuous foothold on a vast, forested continent. At that time, the combined population of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay was around 25,000 colonists, scattered along a narrow coastal strip and surrounded by powerful Native nations.

Saugus (Lynn): Status and Generosity

The Freemans first settled in Saugus (later named Lynn) in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. They were quickly recognized as people of standing. The History of Lynn records:

“This year (1636) many new inhabitants appeared in Lynn, and among them worthy of note, Mr. Edmund Freeman, who presented to the Colony twenty corselets, or pieces of plate armor.”

That Edmund is called “Mr.” here is significant; in the colonies, only about one in twenty men were given that title.

Soon after arrival, Edmund wrote to Governor John Winthrop of Massachusetts about leftover provisions from the voyage:

“Sir, I desire you to be pleased to retain for us Mr. Geere’s part [he died of smallpox on the journey] and my part of the provisions left of the undertaker which you have bought of Henry Troute. Our part is the eight part which I do desire you to retain in your hands, yours to use.”

This small letter shows Edmund already operating as a man of business, negotiating shares and provisions in a new world.

Led by Edmund Freeman, these ten settlers journeyed from Saugus (present-day Lynn) to the shores of Cape Cod, where they established the first town on the Cape under the authority of Plymouth Colony. The plaque, displayed just outside the entrance to the historic meeting hall, preserves the names of the men whose leadership, labor, and resolve laid the foundations of Sandwich, Massachusetts.

Into Plymouth Colony: Toward Sandwich

By 1636–1637, Edmund and Elizabeth Freeman moved from Massachusetts Bay Colony to Plymouth Colony, living briefly in Duxbury, where Edmund was admitted as a freeman on January 23, 1637. Freemanship signaled that he was considered an upright, debt-free, responsible man–someone fit to vote, hold office, and shape colonial policy.

He soon took part in the governance of Plymouth, serving once on the Grand Jury, tasked with “inquiring of all abuses within the body of this government.”

At this time, Plymouth’s leaders–including Governor William Bradford–were struggling under the weight of personal debt to investors such as John Beauchamp. Edmund’s presence offered them an opportunity: by supporting a new settlement led by John Beauchamp’s trusted brother-in-law, they might help satisfy their creditors and strengthen the colony at the same time.

On April 3, 1637, the Plymouth Court granted permission:

“It is also agreed by the Court that those ten men of Saugus shall have liberty to view a place to sit down and have sufficient lands for three score families….”

Edmund was the principal among these “Ten Men of Saugus.” Five, including Edmund, were men of means; the other five were younger, physically strong men prepared for hard labor. Together, they led about 48 additional families along Indian trails onto Cape Cod, roughly 27 miles south of Duxbury, to found the town that would become Sandwich – the first town on Cape Cod, incorporated officially in 1639.

Founding Sandwich: Land, Church, and Community

As principal agent of the expedition, Edmund Freeman II received the largest land grant–about 42 acres of fields and meadow, plus access to salt marsh for hay. Early Sandwich offered rich natural resources:

- Six beaches along Cape Cod Bay,

- Small ponds and rolling hills,

- Forests of pine and oak,

- And a tidal inlet known as Old Harbor Creek, once a safe anchorage for ships.

The first dwellings were crude huts; within a few years, Sandwich became a thriving community, and Edmund Freeman built a comfortable home for his family. Like nearly everyone around him, he farmed and raised animals. For a man trained as a lawyer and used to rental income in England, this shift to frontier farming must have been dramatic.

For Elizabeth Freeman, life changed even more. In England she had servants; in early Sandwich she, like other “goodwives,” likely made soap, candles, clothing, and most household necessities with her own hands. Luxuries were left behind for the sake of religious conviction and a chance to build a godly community.

The Freemans were active supporters of the town’s religious life. They contributed money toward building a meetinghouse and toward the support of a minister. Safety remained a constant concern: colonists feared not only conflict with neighboring Native peoples but also wolves and other predators. Every man was required to have a working musket; in 1639, Edmund was fined 10 shillings for failing to keep his musket in proper readiness.

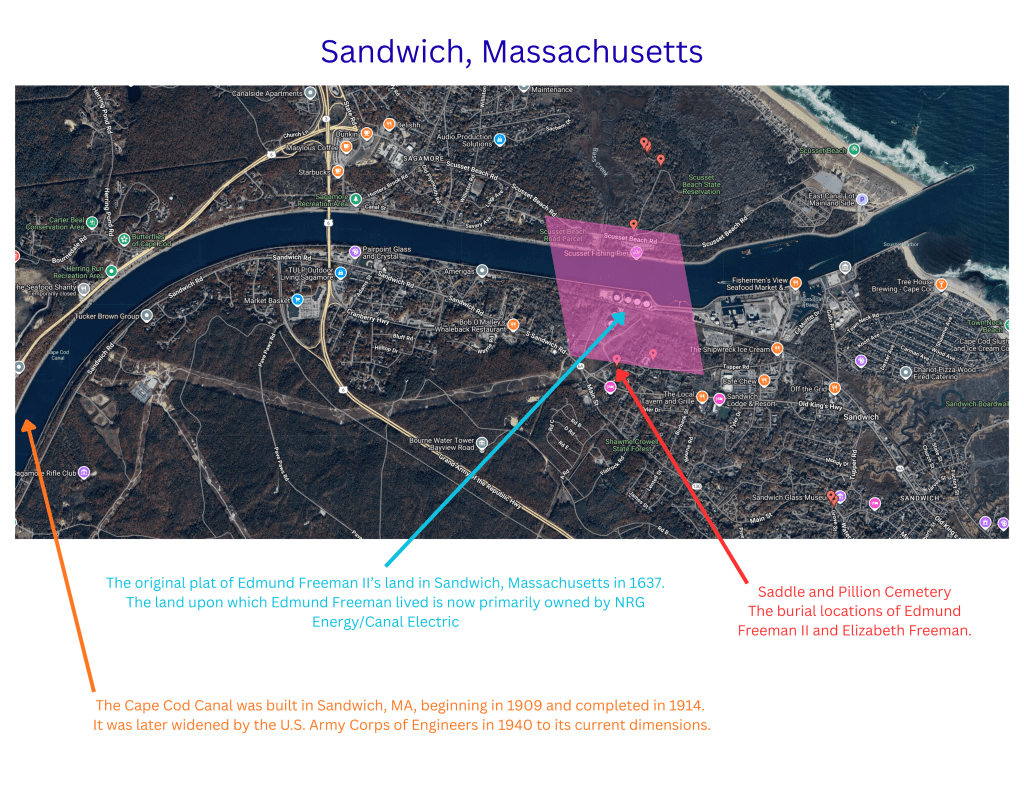

In the 1950s, town historian Russell Lovell sought to have the house added to the National Register of Historic Places, recognizing its singular importance as one of Sandwich’s earliest and most historically meaningful structures. His efforts were ultimately opposed by Canal Electric, which by then controlled much of the former Freeman farmland.

Only a decade later, in 1965, the company constructed the Canal Electric Power Plant directly on the original Freeman land grant—forever altering the landscape first settled by the town’s founding family.

Public Service: Assistant Governor and Magistrate

Beginning in 1640, Edmund’s responsibilities expanded beyond Sandwich. At age 44, he was appointed Assistant Governor, first under William Bradford and later under Edward Winslow–effectively the vice-president of the colony. He served in this high office until June 1645.

In addition, he served as one of three magistrates for the Cape Cod towns, empowered to hear cases where penalties did not exceed 20 shillings. He sat in judgment over disputes and criminal matters, enforcing the colony’s laws as they stood–some of which now seem harsh. In 1641, for example, he “saw a maid whipped for stealing at Barnstable” and later that year witnessed the punishment of Anne Lynceford and Thomas Bray for adultery at Yarmouth.

In September 1642, he joined a Special Council of War on Indian Matters, part of a broader alliance among the New England colonies to coordinate defense. He worked closely at times with Captain Myles Standish, including on cases where colonists were required to compensate Native people for damages–such as paying for a deer or for a hole shot through an Indian kettle. In 1655, he wrote to the General Court urging that colonists pay for damage their horses had done to Native cornfields.

Even while he enforced the law, Edmund himself occasionally ran afoul of it. In 1641 he was fined for lending a gun to an Indian and for keeping swine unringed (allowing them to roam). These episodes humanize him: a man of conviction, but also fallible.

The Plymouth Debts and Strain of Leadership

Throughout the 1640s, Edmund Freeman II also acted as one of three colonial agents for the London investors, including his brother-in-law John Beauchamp. The investors claimed Plymouth still owed them £1,200. Edmund, with his legal training and personal ties, was an obvious intermediary.

In 1645, he again received power-of-attorney from John Beauchamp and began raising funds by securing pledges from individual colonists against their lands and houses. This put him in an awkward position: bound by duty to his brother-in-law and the investors, yet living among neighbors now pressed for payment.

Finally, in 1646, five remaining debtors–including Governor Bradford–transferred lands in Plymouth to Edmund in settlement of the debts. Edmund, in turn, likely transferred money or his own English lands to satisfy the London creditors.

By this time, the burden of mediation and the colony’s internal religious tensions were taking a toll. Edmund favored a proposal that would have allowed greater religious toleration, particularly in places like Sandwich. The measure failed. From then on, the colony tightened its grip: people were fined for missing church, associating with Quakers, and other perceived offenses.

Not long after, Edmund withdrew from high colonial office. It may have been partly political–Edward Winslow later suggested that Edmund’s “Anabaptistry & separation” from some Puritan practices made him suspect–and partly exhaustion from years of conflict.

A Champion of Toleration: Quakers and Controversy

In 1651, Edmund and Elizabeth–now in their fifties–were fined along with eleven others for failing to attend public worship regularly. Many in Sandwich disliked their minister, and when he left, they went without a settled pastor for twenty years.

Religious dissent deepened with the arrival of the Quakers. Quakers shared some Puritan criticisms of the Church of England but went further, emphasizing direct personal experience of Christ, rejecting formal clergy, and refusing to swear oaths, bear arms, or show deference to earthly authorities. To Puritan magistrates, this seemed dangerously subversive.

Quaker missionaries reached New England in 1656 and soon appeared in Plymouth Colony. The authorities responded with harsh laws:

- Fines and imprisonment for those who sheltered Quakers,

- Seizure of vessels transporting Quakers,

- And, in Massachusetts Bay Colony, even execution.

Despite this, two Quakers began preaching in Sandwich, and about eighteen families joined what became one of the earliest and longest-lasting Friends’ Meetings in America.

Edmund’s own family stood at the heart of this movement. His step-daughter Mary (Elizabeth’s daughter from her first marriage) married Edward Perry, a Quaker convert, without being married by the local magistrate, Thomas Tupper–my 11th great-grandfather–as the law required. Instead, they took vows before God and their community, following Quaker practice.

The Plymouth Court reacted strongly, fining Edward Perry £5 each quarter he refused to comply and stripping Thomas Tupper of his authority to marry couples in Sandwich. The court almost certainly viewed Edmund Freeman II with suspicion for allowing such a “breach” within his own household.

The colonial government pressed local officials to enforce anti-Quaker laws. The Sandwich constable, knowing Edmund’s sympathies and family connections, insisted he help collect fines and enforce punishments. Edmund refused. For his non-cooperation, the Court fined him 12 shillings, but the penalty did not change his behavior. To the end of his life, he consistently supported conscience and tolerance over coercion.

Land, Family, and Later Service

While public office diminished after the mid-1640s, Edmund remained important in Sandwich. He was elected constable in 1651 and, later, both he and his son Edmond Freeman III served as selectmen (equivalent to town councilors) in the 1670s and early 1680s.

He continued to be an active landholder and businessman, buying and selling parcels, including land purchased from Native people. A significant episode occurred between 1647 and 1651 over the distribution of salt-marsh land. Latecomers argued that early arrivals–especially Edmund, as the largest proprietor–held land too close to town, forcing newer families to travel long distances. To ease tensions, Edmund sold his original grant to the town and was reimbursed, later receiving different acreage to support his children and grandchildren.

By the 1670s, Edmund was an old man, but still respected. In 1676, during King Philip’s War, he was asked–at around 80 years old–to help recruit Native allies on Cape Cod to protect threatened towns. That he was trusted with such work speaks volumes about his reputation.

About half of the settlements in Massachusetts were destroyed or abandoned during the fighting.

Elizabeth’s Death and a Remarkable Gravesite

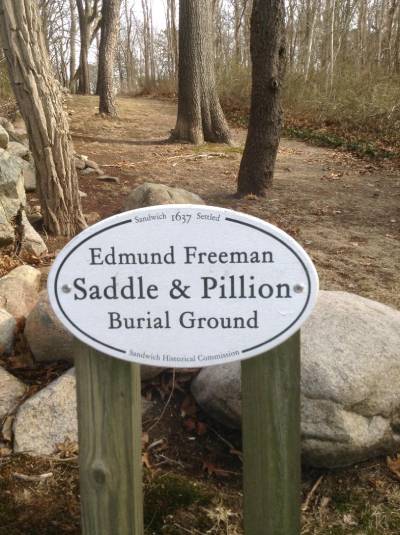

Elizabeth, his steadfast partner in faith and hardship, died on February 14, 1676, aged 77. Edmund chose a burial place on a rise of his farmland and marked her grave with a large stone shaped like a saddle blanket or pillion, evoking years of travel together when husbands rode in the saddle and wives behind.

He instructed his sons and grandson Matthias Ellis:

“When I die, place my body under that stone. Your mother and I have traveled many long years together in this world, and I desire that our bodies rest here till the resurrection. And I charge you to keep this spot sacred, and that you enjoin it upon your children and your children’s children, that they never desecrate this spot.”

A substantial wall was built around the simple monuments. The site–now known as the Saddle and Pillion Cemetery at the end of Wilson Road–is still maintained in Sandwich today.

Named for the distinctive saddle-shaped stones chosen by Edmund to symbolize the miles he and Elizabeth traveled together in life, the cemetery stands today as one of Sandwich’s most sacred historic sites—a quiet testament to the town’s beginnings, its early families, and the enduring legacy they left upon Cape Cod.

Death and Legacy

Edmund Freeman II died in 1682, around 86 years of age. By then he had:

- Given up a secure, wealthy life in Sussex to face the unknown in a precarious colony,

- Helped found Sandwich, the first town on Cape Cod,

- Served as Assistant Governor and magistrate,

- Mediated between Plymouth and its London financiers,

- Advocated for religious toleration long before it became an American ideal,

- And provided land, security, and a moral example for a large and growing family.

One contemporary description sums up how he was remembered:

“Pre-eminently respected, always fixed in principle and decisive in action, nevertheless quiet and unobtrusive, a counselor and leader without ambitious ends in view, of uncompromising integrity and of sound judgment, the symmetry of his entire character furnished an example that is a rich legacy to his descendants.”

Through Puritan settlers, colonial farmers, Revolutionary-era families, and pioneers of the American heartland, this lineage reveals a remarkable legacy—an enduring thread of resilience, faith, and fortitude carried across eleven generations.

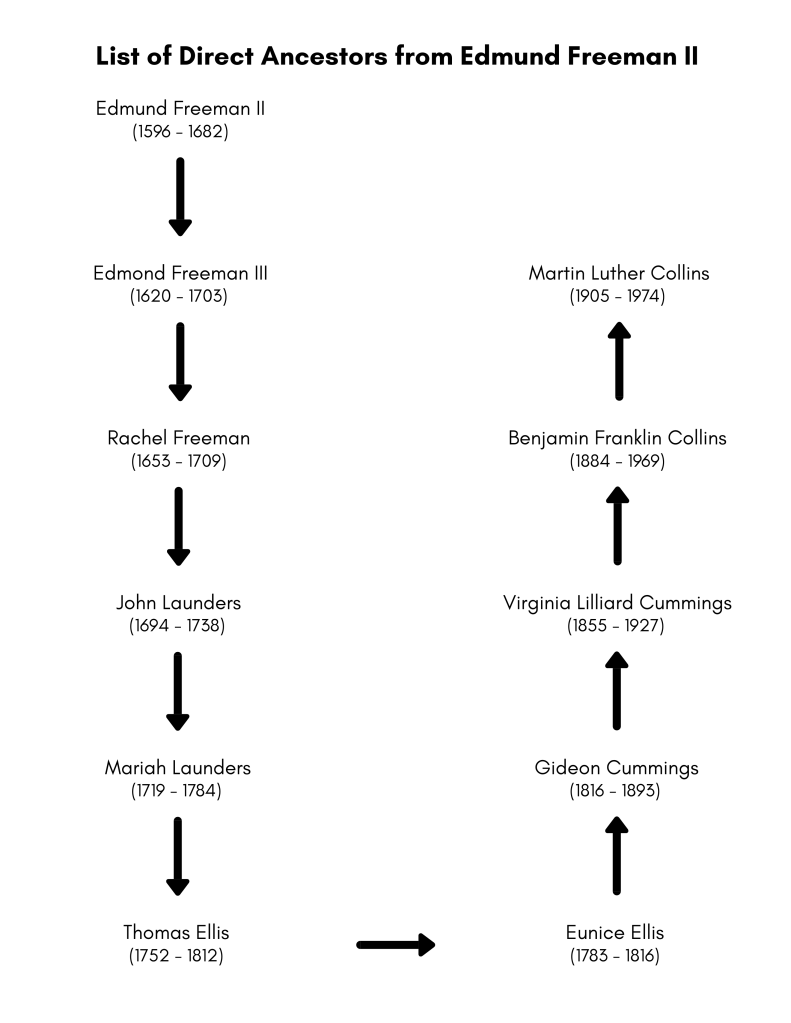

For me, that legacy is personal. When I trace the line from my own life back through my mother, my grandmother, Martin Luther Collins, Benjamin Franklin Collins, Virginia Lilliard Cummings, Gideon Cummings, Eunice Ellis, Thomas Ellis, Mariah Launders, John Launders, Rachel Freeman, Edmond Freeman III, and finally to Edmund Freeman II, I see not just names and dates but a continuous thread: courage in the face of uncertainty, stubborn integrity, and a persistent belief that conscience matters more than convenience.

It is an honor to call Edmund Freeman II my 11th great-grandfather.

The outline of Freeman’s early farmland—once stretching across salt marsh, meadow, and woodland—now intersects with the twentieth-century engineering of the Cape Cod Canal, reshaping the very ground first settled by the town’s principal founder. Marked prominently is the Saddle and Pillion Cemetery, the secluded burial ground where Edmund and his wife Elizabeth Freeman rest beneath the saddle-shaped stones he chose to symbolize their lifelong journey together.

Leave a comment