(1546 – 1595)

My 13th great-grandfather through my great-grandfather, William Jennings Bryan Orr, was Thomas Digges.

Thomas Digges was a remarkable figure whose life and work marked a turning point in the transition from the medieval worldview to the scientific revolution of the Renaissance. His legacy helped to shape the course of human understanding.

Born in 1546 to Leonard Digges and Bridget Wilford, Thomas grew up in an environment steeped in mathematics, science, and the intellectual currents of his time. His father, Leonard Digges, was a respected mathematician and surveyor, known for his advancements in optics and for being a strong supporter of Elizabeth Tudor’s claim to the throne. Leonard’s early death when Thomas was just 13 years old profoundly impacted his son’s future, thrusting him into the care of the Royal Court, where he would become a ward under the watchful eye of William Cecil, the 1st Baron Burghley, one of Queen Elizabeth I’s closest advisors.

Under Cecil’s patronage, Thomas Digges was placed in the care of John Dee, a polymath whose interests spanned mathematics, astronomy, astrology, and the occult. John Dee, who served as Queen Elizabeth’s chief astrologer, was a man who did not distinguish between astrology and astronomy — a common conflation in those times when the stars were seen as both mystical and scientific entities. John Dee took charge of Thomas’s education, likely sending him to Queen’s College at Cambridge University, where Thomas Digges immersed himself in the study of mathematics and military sciences.

Despite his position as an astrologer at Elizabeth’s court — a role he inherited after John Dee’s retirement — Thomas Digges was far more interested in the emerging science of astronomy. Astrology, with its roots deep in medieval superstition, was beginning to lose its grip on intellectual circles as the Renaissance brought a renewed emphasis on empirical observation and rational inquiry. Even as Thomas Digges cast horoscopes and made predictions in accordance with courtly expectations, his true passion lay in the stars, not as omens, but as objects of scientific study.

At a time when the Ptolemaic geocentric model still dominated, Thomas Digges became one of the first Englishmen to openly support and advocate for the heliocentric theory proposed by the Polish mathematician and astronomer, Nicolaus Copernicus. This theory, which placed the Sun rather than the Earth at the center of the universe, directly challenged the geocentric model long upheld by the Catholic Church. When Elizabeth ascended the throne, Copernican ideas were still controversial, but they were gaining traction among the educated elite, including Thomas Digges, who became the leading proponent of this new cosmology at court.

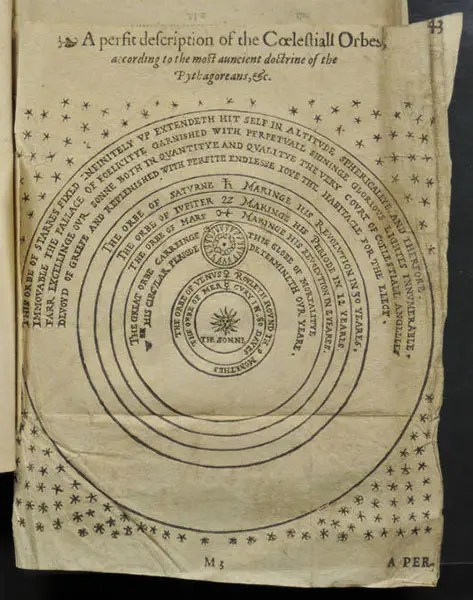

In 1576, Thomas Digges published an annotated version of his father’s book, A Prognostication Everlasting of Right Good Effect, with addendums written by him, where Thomas Digges first publicly supported the Copernican model. The almanac was immensely popular, not only for its predictions about weather and farming — much like today’s Farmer’s Almanac — but also for its radical ideas about the cosmos. It was within this work that Tomas Digges included his famous diagram of the Copernican universe. This diagram was Thomas Digges’s most significant contribution to astronomy.

The diagram extended the boundaries of the universe to infinity, filled with countless stars — a radical departure from the finite, enclosed cosmos of medieval thought. This concept of Thomas Digges’s was a bold departure from even Copernicus’s own model, which still maintained that stars were positioned at a fixed distance in a single sphere surrounding the solar system.

Thomas Digges’s proposal of an infinite universe was utterly groundbreaking. He theorized that stars extended into space at various distances, an idea that would later form the foundation for the modern understanding of an expanding universe filled with countless galaxies. Although it would take centuries for the full implications of his ideas to be realized, Thomas Digges had already set the stage for a profound shift in human understanding of the cosmos.

In addition to his astronomical work, Thomas Digges’s education in military sciences and his position at court led him to apply his knowledge to practical matters, particularly in the defense of England.

William Cecil, concerned with protecting the British Isles from invasion, relied on scientific advancements to strengthen the Navy and improve intelligence. The Dover cliffs, from which one could just barely make out the distant shores of France, presented a challenge for spotting incoming fleets. This challenge spurred Thomas Digges’s interest in optics, leading him to experiment with the Camera Obscura — a device that projected images through a small hole to create clearer pictures of distant objects. While Thomas Digges did not invent the telescope, his “perspective glasses” functioned similarly over short distances, and his work laid important groundwork for future developments in telescopic technology.

Thomas Digges’s legacy as a scientist was also shaped by his religious convictions. A conservative reformer, he worked to steer the Church of England away from its reliance on astrology, advocating instead for a faith that embraced the emerging sciences. By the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, the Church had grown increasingly suspicious of astrology’s claims, and Thomas Digges’s efforts contributed to this shift.

Tragically, Thomas Digges’s life was cut short when he contracted an illness while on a mission to the Low Countries (modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands), where he had been sent to oversee work. He returned to England, but on August 24, 1595, he passed away, leaving behind a legacy that would echo through the centuries.

Thomas Digges’s contributions to astronomy, particularly his vision of an infinite universe, positioned him as a key figure in the transition from a world governed by astrology and superstition to one increasingly shaped by science and reason. His work not only challenged the prevailing views of his time but also laid the groundwork for future generations to explore the vast, star-filled expanse of the cosmos.

This is the very first printed image to depict a universe that “infinitely up extendeth,” as Thomas Digges proposed in his caption to this diagram from A Prognostication Everlasting of Right Good Effect, revised and edited by Thomas Digges, 2nd edition, 1596.

Sources:

Thompson Cooper, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 15, Digges, Thomas, London, Oxford University Press, 1921.

Francis R. Johnson, Astronomical Thought in Renaissance England: A Study of the English Scientific Writings from 1500 to 1645, Johns Hopkins Press, 1937.

Stephen Johnston, John Dee: Interdisciplinary Studies in English Renaissance Thought, International Archives of the History of Ideas / Archives internationales d’histoire des idées, vol. 193 (Dordrecht: Springer, 2006).

Martin Kugler, Astronomy in Elizabethan England, 1558 to 1585: John Dee, Thomas Digges, and Giordano Bruno, Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry, 1982.

Leave a comment